Hera of Lexington

Chapter 4 (Read Chapter 1)

by Anta Baku

They were still nine days from Cumberland when Jean came onto the bridge during Hera’s watch, stretching their arms.

“Done,” said the priest. “We’ve finally gotten the whole thing digitized.”

“I’m impressed,” said Hera. “I thought it would take you the whole trip.” The papers from Sage’s hermitage took up an entire room in the crew quarters, and Jean had taken on the task of turning them into readable files, with the help of Shale.

“I thought it would take longer,” said Jean. “About halfway through I stopped trying to understand things, and then it went faster.”

“So you’ve digitized it, but you haven’t actually read it?”

“I’m sure Shale has,” said Jean. “Ask them for a summary if you want. I just came up to tell you we’re finished, and beg off my next watch. I need to sleep for about a week.”

“We’ve got a week,” said Hera. “And you know how boring the watches have been out here.”

“I’ve gotten a lot of work done during them,” said Jean.

“I’ll give yours to Shale,” said Hera.

“Won’t Alistair throw a fit?”

“I’m pretty much tired of Alistair’s fits,” said Hera. “If he still doesn’t want Shale to take a watch, he can double-shift himself.”

“Then Shale will be watching anyway, cause they don’t trust Alistair not to fall asleep.”

“Works for me,” said Hera.

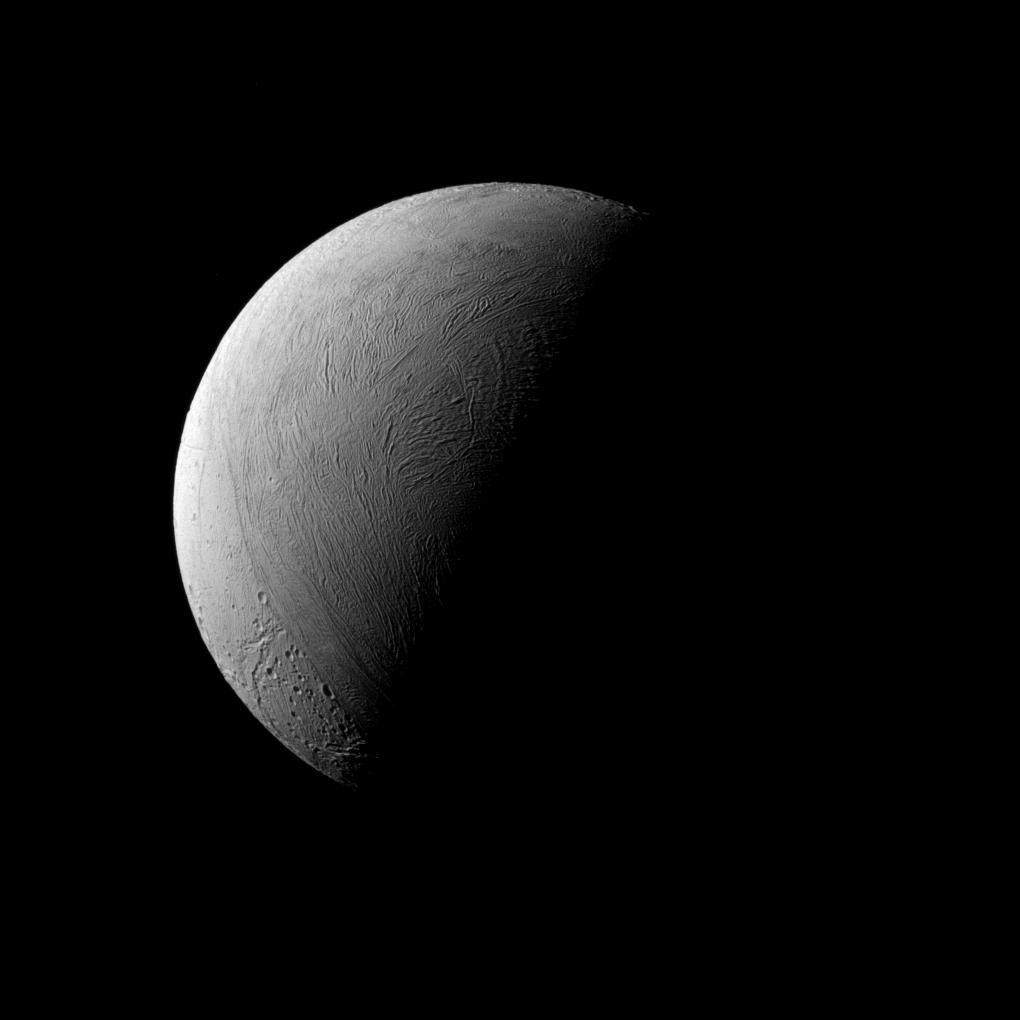

Cumberland had been visually available for a while, but it was just this watch Hera was able to get a glimpse of Eddy, the satellite where they were headed. The gas giant Cumberland was beautiful, but it was still good to see something else, besides the lines of artificial pinpoint lights revealing the shipping lanes in and out of the Lexington system. Everything was regimented out here, precisely on beacon, no ships allowed to get close enough to each other to see a disk, much less make out details or interact. The designers of Eddy’s traffic control system weren’t taking any chances of accident, and space was very, very big.

There was the usual container ship and cruise ship chatter on the radio, complicated by several seconds of lightspeed lag between each position in line. Fred liked to listen to it on his watch, and sometimes even join in with lighthearted comments that weren’t always appreciated. Hera didn’t see the point; she preferred leaving the bridge quiet.

Just weeks ago they had been here, dropping into the system from their raid on Shale’s space station, dumping their waste heat at Eddy’s collection facilities, and moving on into the inner system, like hundreds of other ships before and after. With no need to take on water or nitrogen, they hadn’t stopped at the moon. Hera couldn’t keep herself from calculating the financial cost of the information they’d acquired in the meantime. Round trips to the edge of the solar system weren’t cheap, and she knew exactly how much they could have saved by knowing then what they knew now. She knew that was impossible, that what she had was a meaningless number, but it was a large one nevertheless.

There wasn’t a separate line for ships who intended to stop at Eddy, so they had to wait for every giant supercarrier, every lumbering, luxurious passenger liner, to take on reactant and launch itself out of normal space. In-system travel wasn’t for the impatient. Hera dealt with it through the meditative nature of long, silent watches. Jean read Sage’s writings into the computer, and spent their breaks in friendly arguments with Fred over the experimental technologies they’d hung onto after the Ticonderoga mission. Alistair drank, and fought with Shale, but at least he’d agreed to do it in his own quarters.

Hera wasn’t sure what Shale was doing with the rest of their time, or even how Shale perceived time. The AI surely had more capacity than the digitization project and the constant sniping with Alistair could account for, but she didn’t understand how that worked. She felt guilty for not having more of a handle on how the newest team member was doing, but both AIs and Gavidarians were notoriously difficult to understand, and Shale was showing that the combination was more than additive. They had given up on ignoring Alistair’s constant jabs and taken to returning them, which oddly seemed to make both of them happier. But it left Hera with less interest in talking to either, in case they tried to extend it to her.

She knew she should be reviewing Sage’s documents, now that they were all available. She knew she should have been doing it in pieces as Shale and Jean got them digitized. But she had never had much appetite for theology, and just couldn’t bring herself to the task. If it weren’t for the Occupation, she would have stayed as far away from the Church as was possible on Lexington, like the rest of her family. Her rough-and-tumble education in religious artifacts didn’t extend to reading the ramblings of divinely-inspired hermits. She’d stolen a few books, but never read them.

But she should know something before they found Sage, if they were lucky enough to do so. Whatever the account of a hermitage did or didn’t have in terms of philosophical value, it was bound to be important when you encountered the former hermit themself. Besides the basic decisions of the Preservation Mission, it was the only access they had to the bishop’s character, and there were hundreds of pages of it. Analysis was Jean’s job, but Hera had a duty as leader to familiarize herself with the material as much as she could.

None of this was convincing her to open the files. Instead she opened the voice channel to Shale.

“Have you read many Lexingtonian religious texts?” she asked. “Is that the sort of thing Gavidarians collect?” The books she’d liberated for the Resistance were always stored together with completely unrelated works, novels, travel guides, things like that. As if the important thing to the Gavidarians was the fact of the books, rather than their content.

“They don’t, particularly,” said Shale. “They’re very interested in book-binding, so I’ve seen some examples, but they don’t even digitize the words.”

“So you’re as new to this as I am, I suppose,” said Hera.

“Oh no, not at all,” said Shale. “The AIs on Vexor Alexi were extremely generous with data about Lexington. And they are very interested in religious texts, and very interested in digitizing them.”

“I’m surprised,” said Hera. “They didn’t seem like people who were eager to give up information.”

“Not normally, I think,” said Shale. “But they wanted me to know where I came from. They were very insistent.”

“I thought you came from a Gavidarian lab,”

“I tried to explain that to them, until I realized it was causing them pain. A human born in a Gavidarian prison is still a human. Still a Lexingtonian, if that’s where their parents were from. The Vexorian AIs feel the same way about me.”

“Do you feel that way?”

“I don’t know,” said Shale. “I’m still thinking about it.”

“Whatever you are, I’m glad to have you here,” said Hera. “I think.”

“Is Alistair giving you doubts?” asked Shale.

“It’s my job to have doubts,” said Hera. “I don’t want to believe Alistair. In fact I don’t want to believe Alistair about anything right now. He’s been even more annoying than usual since you showed up. But I don’t have the luxury of believing things because I want to. I have to think about what happens if I’m wrong.”

“And you could still be wrong about me.”

“I could always be wrong about anyone,” said Hera. “You don’t have any way to prove yourself except by being a part of the team, and so far you’ve been a useful and cooperative part of the team. I have to worry about what happens if that changes. That doesn’t mean I expect it to. I hope you’ll be with us to the end of this, wherever that ends up being.”

“So do I,” said Shale.

“So maybe we can let that go for a bit,” said Hera. “Tell me something about religious texts, and about Sage.”

“There are three core concepts to Milosianism on Lexington: Truth, Compassion, and Resolve.”

“I know that much,” said Hera. “My family isn’t religious, but we go to festivals.”

“Hermitage texts tend to either be formulated around a single one of those concepts, or to address all three of them. In fact, of everything Vexor Alexi gave me, there are only two examples of a complete text that contained two.”

“So which was Sage’s?”

“We don’t have a final manuscript, so it’s hard to say anything definitive. But they were working on a format that referenced all three core concepts.”

“A generalist, then, I suppose,” said Hera. “Is there anything of particular interest? That you could explain to me?”

“I’m not sure how to communicate what’s of interest without teaching you Milosian theology from the beginning,” said Shale. “Sage has a lot of thoughts about the Gavidarians that are not especially valuable. They didn’t know very much about Gavidarians, and knew nothing about the results of the invasion. Most of what they wrote has already been surpassed by hermitage writings made by priests during the Occupation, priests who had first-hand experience.”

“So this document won’t be particularly important to the priests at home?”

“I’m not sure,” said Shale. “Jean seemed to think there were parts of it with insights that would be welcomed by the current religious authorities. Maybe Jean could explain them to you. But overall, I don’t think Sage’s manuscript is going to be of theological significance. Historical, maybe, as the writings of the head of the Preservation Mission. But they kept out any mention of the fate of the Relics, and there’s no secret messaging that Jean and I could find.”

“You’re saying it’s just the ramblings of a second-rate theologian stuck by themself on a hostile planet.”

“I wouldn’t like to stand behind that characterization of a person I haven’t met,” said Shale. “The documents we have are not especially insightful, and the parts of them that were once unique have already been superseded by later work. But Sage may not have finished. If they came here, seven years ago, and were able to get access to modern hermitage texts, to experience Gavidarians for themselves, they may have revised the text significantly.”

“I’m not really interested in the value of Sage’s theology,” said Hera. “I’m interested if the text can tell us anything useful.”

“Unless you want a first-hand account of the earliest moments of the Occupation, I think you will be disappointed,” said Shale.

“I have one of those of my own,” said Hera. “I don’t need another.”

Jean was more optimistic at their next shift change. The priest hadn’t slept for a week, but stayed off watch for five days, resting and reflecting on what they knew about the manuscript. By the time they were ready to take a watch again, Eddy was an icy-white ball on the viewscreen, and they were even close enough to make out the end of the line, where ships took on water and began their trajectories to lightspeed.

Shale’s first official watches had been uneventful, and Alistair seemed somehow disappointed that the betrayal he had been anticipating never materialized. Hera was just as glad.

“What did Shale say?” said Jean. “Theologically negligible?”

“That was the short summary,” said Hera.

“They’re not wrong, I guess,” said Jean. “There’s nothing in there that’s revolutionary, nothing that will make this one of the essential hermitage texts, or even the well-read ones. I could be the only human to ever read the whole thing. Other theologians will look at the AI notes and decide it isn’t worth their time.”

“But does it tell us anything useful?” said Hera. “I’m not concerned with theology, I’m concerned with finding Sage.”

“They’re essentially orthodox,” said Jean. “Especially for someone who chose to be named Sage. It confirms my personal impression that the name was aspirational, rather than descriptive. They wanted to have theological talent, but I don’t think they really did. The parts of the notes that aren’t about Gavidarians are mostly looking for something to say, not the notes of someone who has a revelation and is trying to figure out how to communicate it.”

“Milo really valued self-awareness,” said Hera.

“Oh, yes,” said Jean. “And as the notes go on, you can tell Sage is gaining some. They’re frustrated by their inability to get anywhere. If the hermitage hadn’t been enforced, I think they might have given up. Most of the section on Resolve is devoted to the question of whether continuing the hermitage is theologically correct.”

“That’s interestingly recursive, at least,” said Hera.

“Oh, you would think so, but Sage was hardly the first to have that problem. A lot of the historical hermitages were even less voluntary. That ground has been very well covered, and Sage had nothing new to say about it. They might have been more successful with access to the previous work. But I don’t think Dae’s archives included a lot of religious texts.”

“Not current ones at least, if the version of Dae we met was representative.”

“Yes,” said Jean. “So they were trying to reinvent Milosianism from memory, essentially. And they had a good memory, but little insight. And without a way to check on whether what they were thinking had been done before, it turned out mostly redundant.”

“And there’s nothing in there that we can use to find them?”

“Not that I can see now,” said Jean. “Maybe there will be something when we get to Eddy, something there that triggers an association for me. Or something that indicates Sage is still thinking about all this, and maybe made some progress once they were back in society.”

“You’re planning to come down to Eddy with me?” said Hera. Jean usually wasn’t one to participate in missions.

“Yes,” they said. “I don’t think there’s any real danger in coming down to the colony, in talking to people there. And maybe I’ll see something that I wouldn’t, watching from the ship.”

“All right,” said Hera. “I guess we can do that. But if things go wrong, you need to get to safety. I can’t fight and protect you.”

“I hope there won’t need to be any fighting at all,” said Jean. Hera wasn’t that optimistic.

In the end, Hera, Jean, and Alistair all landed on Eddy. Hera was half annoyed with Alistair for insisting on coming along, and half glad to have twice as much protection for Jean. And she had to admit the validity of his point that they didn’t know what they were getting into and might need social engineering just as much as tactics and situational analysis.

Eddy hadn’t rebuilt a government after the Occupation yet. The authorities in the system in general were concerned with the continued smooth operation of the FTL fuel system, but as long as that was maintained, there weren’t enough resources to worry about how the population handled itself. So there was no central authority to present themselves to, and no one to direct them after landing. Presumably there would have been a liaison if they were visiting the fueling facility, but anyone who wanted to come here for any other reason was presumed to know what they were doing.

Shale had been watching local broadcasts, and reviewing travel guides. They directed the trio to a central market, which seemed to be the social hub for the local population. It wasn’t much of a market, by central-system standards. Most of what was available here was vegetables. And most of the people selling were geriatric, a generation or more older even than Jean. There were few buyers at this hour, but they at least represented a larger mix of ages. Otherwise Hera might have thought there was no one young here at all.

They didn’t have long to think about who to approach, because their entrance caused a sensation. Or more properly, Jean’s entrance did. Hardly anyone was interested in Hera or Alistair, but they crowded in on the priest, all talking excitedly at the same time. All these old people didn’t seem much of a threat, and Hera estimated it would probably be more dangerous to treat them like one. Her first impression was that Eddy wouldn’t be a good place to be rude to your elders.

She gradually picked up the tone of the conversation, or the one-sided talking from a dozen sources. Jean was doing their best to respond, but wasn’t having any easy time making sense of the whole thing. Hera, outside of it, was in a better position to get the whole picture. Eddy, or at least its elder population, was excited to be visited by a priest. She figured Jean would be able to handle that, and looked around for anything unusual in the situation.

One elderly woman had not rushed up to the newcomers, but was still arranging summer squash in her stall and looking on. She was small, and had a slight smile on her face, but Hera couldn’t tell if it was sardonic or wistful. Leaving Jean and Alistair to handle the crowd, Hera approached her.

“You’re not excited?” she asked.

“I was born on Lexington,” said the woman. “I’ve seen a priest before.”

“And these people haven’t?”

“There hasn’t been a priest on Eddy since the Gavidarians came,” said the woman. “And I doubt one so important as to renounce gender has ever been here.”

An old man had drifted away from the crowd to listen in on them. “There was, once,” he said. “When they first built the water system, a bishop came to bless it. There were all sorts of important people here, then. I remember, I was seven.”

“You haven’t seen a bishop since then?” said Hera.

“A bishop?” said the woman incredulously. “What would a bishop want to do here? We grow food, melt ice, ship out water. The people here are religious, but they’re religious on their own. It’s a simple life, and we get by well enough without even a priest. If you’ve come to stay, you’re too important for this place by half.”

“We haven’t come to stay,” said Hera. “We’re looking for a bishop who might have fled here during the Occupation.”

“And who’s asking, I might say?” said the woman. “Come here looking for a bishop and won’t even introduce yourself?”

“I’m sorry,” said Hera. “My name is Hera, and I work for the Lexingtonian Church. My job is to look for artifacts lost in the occupation.”

“A bishop is an artifact?”

“They might know where some were lost,” said Hera. “Now why not give me your name, friend.”

“I’m Zita,” said the woman. “And I’m not sure I’m your friend. But there are no bishops here. Not even an acolyte, in all the years I’ve lived here.”

“They might have been in hiding,” said Hera. “From the Gavidarians at least.”

“We wouldn’t have given anyone up to the Gavidarians,” said Zita. “Besides, they didn’t bother us much. Well, I wasn’t here when they took the priests and the government. The clans handled themselves, and didn’t give the conquerors any trouble. They kept to the water system, like the Lexingtonians do now.”

“You didn’t help the Resistance?” said Hera.

“Of course we helped the Resistance!” said Zita. “And I’m more convinced I’m not your friend. We gave them food. We hacked into the records to get Resistance ships in and out of the system. Until they caught the girl who was really good at that. But she kept retribution away from us, even then, somehow. We were more valuable to the Resistance as non-violent assets. It wasn’t always easy to convince the younger ones of that, but people listen to their clan elders here. Especially after the end of the government.”

Shale pinged her. “The girl she’s talking about is Nike,” he sent. She sent back an acknowledgement. She’s been able to figure that out herself.

“If a priest did come here,” she said, “there wouldn’t be anywhere for them to hide?”

“Not with us,” said Zita, and the old man nodded agreement. “Not on the surface, obviously, unless it’s a priest that can breathe nitrogen and stay alive close to absolute zero.”

The old man spoke up. “Maybe in the water treatment plant?”

“Now that’s an idea,” said Zita. “We might never know if someone was hiding in the water treatment plant.”

“Wouldn’t the workers have seen them?” said Hera.

“Oh, no,” said Zita. “There haven’t been human workers in water treatment for longer than I’ve been here. The Gavidarians brought in their own workers, and when Lexington took over again, they just changed supervisors and kept the whole thing going.”

“I worked in water treatment when I was young,” said the old man. “But now it’s only farming.”

“But if humans don’t work in water treatment, who does?” said Hera. “Surely there aren’t still Gavidarians here?”

“Oh, no,” said the old man. “All the work is done by the Hoozu.”

Hera must have had a blank look on her face because Zita said “you didn’t know about the Hoozu?”

Hera settled herself down for a second before asking the obvious question. “What’s a Hoozu?”

It wasn’t a joke. The Hoozu were amphibious animals, brought in by the Gavidarians for more efficiency at running the FTL supply system. Rare minerals had to be extracted from the water before it was piped to orbit and loaded onto FTL ships, both because it would make the drives less efficient and because the products were valuable. Hoozu could breathe underwater, and were better at the resource extraction than humans had ever been.

At least, that was the theory. Hera couldn’t find anyone in the Eddy community who had ever seen a Hoozu. All they had were rumors, stories from system managers who came into town occasionally to shop for food. The humans who were running the FTL system now kept to themselves almost as much as the Gavidarians had. Hera wondered if the Hoozu were a fraud perpetrated on the naïve populace by bored system employees. But one thing was for sure: no one here knew very much about what went on in the water treatment complex. If somebody was hiding on Eddy, that was the most likely place.

Hera bought two bags of vegetables to keep the community happy, one from Zita and one spread out among the other stalls. They were going to be eating a lot of summer squash and eggplants on the ship, on the way to wherever they were going next. But for now Hera wanted to talk about getting into the water treatment facility.

Shale had both a blueprint of the facility and a bunch of general information about the Hoozu. Hera had the AI send off the blueprint for Alistair and Fred to review, while she learned about the unexpected aliens.

“I don’t know anything about the specific group here,” said Shale. “But Gavidarians use Hoozu workers throughout their empire.”

“Have you ever met one?”

“No. They’re amphibious. They wouldn’t do well aboard a Gavidarian space station.”

There wasn’t much in the records to indicate what a Hoozu group might be like on Eddy. Gavidarians apparently didn’t use them in similar facilities elsewhere in their empire, which made sense. The Gavidarian lightspeed drive didn’t work on the same principles as the one used by most mammalian civilizations, and Lexington was the first civilization they conquered that was already FTL-capable. There were water reservoirs for commercial traffic in and out of Gavidarian space, but on a much smaller scale.

The records mostly concerned large colonies of Hoozu used to grow food for the Gavidarians’ mammalian slaves, and also used as food for the Gavidarians’ mammalian slaves. Gavidarians had discovered rice almost as soon as they’d discovered slavery, and the two went well together. Gavidarians themselves had little use for swampy and flooded land, so when they found out they could use it to feed their slaves they were more than willing to designate it for that purpose. Hera saw records of Hoozu tending rice, but also cranberries, cress, and lotus, as well as dozens of aquatic species which didn’t originate on Earth.

“The Gavidarians have trained the Hoozu to grow an almost-nutritionally-complete array of food crops,” said Shale.

“Almost?”

“It’s lacking in protein. But when they need protein, they just butcher a Hoozu.”

“That’s creepy,” said Hera. “They’re agricultural animals, but they’re also agricultural animals?”

“I don’t understand,” said Shale.

“They grow food, but they’re also grown as food,” said Hera. “Are they intelligent?”

“I don’t know,” said Shale. “They’re skilled. But are they more skilled than something like a horse, or a dog? The Gavidarians aren’t very interested in researching whether animal species are intelligent.”

“They enslave everyone equally,” said Hera.

“Something like that.”

Hera was still thinking about that when Fred and Alistair returned with a plan for getting into the water treatment facility. Fred had one of his fake ID packages all drawn up for her, indicating that she was a senior assistant to the Inspector General, here for a surprise technical review. The identity looked solid, but Hera wasn’t sure.

“I’m not here to do a technical review,” she said. “I might be able to fake a technical review, but I’d spend the whole time looking at the wrong things.”

“There aren’t a lot of people who have legitimate access,” said Fred.

“Who else besides the Inspector General?”

“Labor Relations, Human Rights,” said Fred.

“Either of those is a great way to get resistance,” said Hera.

“I don’t know anyone else who could show up unannounced,” said Fred. “I think we’re stuck with the office of the I.G.”

“Wait, try this,” said Hera. “What if I was an investigative agent of the religious authorities, looking for people lost in the Occupation, and I think one might have hidden out here?”

“You want to go in as yourself?” said Alistair.

“I keep trying to tell you, this isn’t the Occupation anymore,” said Hera. “We’re allowed to tell people the truth, sometimes.”

“It might work,” said Fred. “But I don’t like it.”

“You sure you don’t just want to avoid wasting a cover identity?”

“I put a lot of work into this!”

“Save it, then,” she said. “We might need it later. For now, we’re going to try telling them who we really are, and see what happens.”

Alistair looked disgusted, but he didn’t fight it.

Half an hour later, Hera was no longer sure that telling the head of the water processing facility who they really were had been a good idea. Oh, it had gotten her into the plant with no trouble at all. But now she was having trouble getting out of the administration office. It turned out that the head of the whole operation was a fan. Hera hadn’t even known they had fans. But apparently her exploits with Fred and Alistair during the Occupation had spread around the outer planets, where that sort of gossip was harder for the Gavidarians to put down, and out here they were still lightly famous even after the invaders had left. Why them, and not the people who had done the actual work of getting the Gavidarians out? She could hardly ask at this point. Besides, it was all the work she could handle just to get out of being given a guided tour.

She explained for the third time that what she really needed was access to the obscure parts of the facility, the back corridors and disused rooms, places official humans doubtless hadn’t been in decades. That she was equipped to handle that sort of thing, and no, she didn’t need any help. But the administrator’s enthusiasm had caught on amongst his employees, and she was swamped with unwanted volunteers. A few of them were interested in Hera’s history, but most seemed to just be excited at the prospect of something unusual to do. Working on Eddy might be important, but it clearly wasn’t exciting.

How was she going to get rid of them so she could do her actual job? Being honest with them about looking for a bishop who was lost in the occupation was one thing; having them milling about destroying the evidence was another. To say nothing about how complicated they would make things if she actually found Sage. There had to be some way to get their attention focused elsewhere.

She pinged Alistair. “I need backup.”

“Already?” he sent back. “It will take me a minute to gear up,”

“No gear,” she replied. “Targets are friendly.” She didn’t mention that they were overly friendly. He could find that out when he showed up. “Just come prepared to talk.”

It would take him a few minutes to arrive, which she covered by telling the story of how they had gotten Archbishop Kiley out of Greensborough just ahead of Gavidarian arrest. By the time she was done, Alistair had arrived, and they segued right into one of his stories, a much more exciting one about seducing a Free Trader to smuggle rebel weapons buyers out of the system. The story was good, and Alistair was always guaranteed to enrapture at least a significant portion of any crowd no matter what he was telling.

Hera had no trouble slipping out the back. Nor did she seem to be at any risk of discovery in the rest of the facility. Even those workers who weren’t fans of the team must have wanted to take advantage of the rare opportunity for a distraction from outside. The offices and quarters she walked past were deserted. She didn’t bother searching them; this part of the facility was too clean for anyone to have been hiding in it for long. She needed to find the parts of it that saw less traffic, or at least less human traffic. The plans Shale had found and sent to her feed just had some open, undetailed rooms labeled “Hoozu” down by the water intakes. If there was somewhere to hide in this building for years, that was the most likely place.

The closer Hera got to those rooms, the dingier and dustier the corridors became. These were still human quarters, or at least they were labeled that way on the map. But when Hera stuck her head into a couple of them at random, they were empty. She pinged a question at Shale.

“The station crew was much larger before the occupation,” the AI sent back.

“You could hide a major temple worth of bishops in this place,” said Hera. “I’m going to have to check all these quarters.”

“You could, but they didn’t,” said Shale. “These quarters still get maintenance checks. They still get cleaned.”

“Not very often,” said Hera. Fred kicked in a meme of a very lazy housemaid.

“I still think the Hoozu are a better bet,” said Shale. “Humans almost never go there.”

“They don’t need cleaning and maintenance?” said Hera.

“Not according to the logs.”

“All right,” she said, and moved on. “I just hope I find something so I don’t have to go through all of these on the way back.”

She made her way through an access door into the more mysterious parts of the plan, a dim corridor where she immediately revised her idea of whether the disused human quarters had been cleaned. It was clear no one had even walked through this corridor in years. Hera worried a little bit about leaving her own footprints in the deep dust, but there wasn’t any other way through. She breathed shallowly and hoped there was cleaner space on the other side.

There was another door at the end, and she had to clean the doorknob with the end of her shirt before she could even get enough grip to open it. It didn’t add much more dust to her clothes than they had already accumulated from walking through the short corridor. But on the other side the floors were clean again, and the walls white and well-lit. She brushed herself off as well as she could, and hoped that whatever was down here wouldn’t expect her to look presentable.

The room here was large, open, and full of turtles. Not quite loose, free-roaming turtles, though. There were clear plastic enclosures, open at the top, with walls about as high as Hera’s knee, in rows throughout the room. They had water in them up to a few inches above the floor. Above the water there were rocks, and high above the rocks were heat lamps. Hera could feel the warmth coming off them, even from the doorway, several feet from the nearest enclosure.

She could also see that each one was full of turtles. Some of them were sunning themselves on rocks, and others were swimming in the water, visible through the transparent walls.

“Hoozu aren’t turtles, right?” she sent back to the ship.

“No, they’re mammals,” Shale replied. “Why?”

“This room is full of turtles,” she said. “Someone is farming them.”

“Maybe that’s what Hoozu eat,” said Fred. “The Gavidarian records weren’t very clear.”

“I suppose if they can farm rice and cranberries, they can farm turtles,” said Hera. “But right now there’s nothing in here but turtles and more turtles.”

“Maybe you should move deeper into the facility,” said Shale.

“Just what I was thinking,” said Hera. She picked an aisle and passed down the row of turtle tanks, headed for an open doorway on the opposite side of the room from where she had entered. Halfway there she sensed a presence, somehow, though she couldn’t see anything. There was a splash from a tank on the next row over from her, and when she turned to it, a dark shape vanishing into the bottom of it, and turtles fleeing onto the rocks.

“The tanks are open on the bottom as well as the top,” she said. “I think that must have been a Hoozu.”

“What did it look like?” said Fred.

“I didn’t see more than a shadow,” said Hera. “It ate a turtle and dived away again.”

Fred sent her a horror-movie meme, which was not helpful. There had been no sign in the Gavidarian records that Hoozu ever ate sentient mammals, but then again, would the Gavidarians have cared? The records were sparse in a lot of places. Hera had a vision of Hoozu, whatever they were like, jumping out of the tanks to attack her. Mostly what they were like in her imagination were giant maws full of teeth. She moved quickly toward the opposite door, but was reluctant to enter.

She told herself that the whole idea was silly, that if Sage was living down here, clearly it was safe for humans. Then again, one possible explanation for Sage’s complete disappearance was that the bishop had gotten too confident and been eaten by the Hoozu.

Nothing to do but go forward, however.

The next room was a giant collective sleeping chamber, and Hera got good looks at a few sleeping Hoozu. There were plenty of teeth, in triangular heads as long as her shoulders were wide, but also arms and legs and tails. The body was maybe a little longer than the proportions of a typical Earth-descended quadruped, and the tail was definitely shorter, but by and large they had a familiar shape. The forearms were splayed for swimming, and both sets of feet were webbed.

The surprising thing about them wasn’t their shape but their color, which was a rich pink, with significant shade variations between individuals. And they were definitely mammals, covered with thick and shaggy fur. If it weren’t for the teeth, Hera might have had trouble confusing them for very large plush toys. But she had no urge to snuggle up to something twice her length and probably five times her weight, especially with those teeth.

There were few enough of them sleeping here that this was probably the night shift, if such a thing made sense for Hoozu. The chamber had alcoves for hundreds of sleepers, but the vast majority of them were empty. It was sparsely furnished. Each sleeping alcove had something of a nest built up in it, out of various soft materials that the Gavidarians must have imported for them especially. Hera didn’t recognize them, and surely nothing suitable could have been found on Eddy. She wondered if they were in need of replacement. How long could a Hoozu sleep on something before it wore out? The sleepers weren’t moving very much, but those bodies had to be hard on materials.

None of the sleeping niches Hera could see from the door looked like they had been redesigned for a human. She’d have to do a more thorough search if she moved through the room, but she doubted Sage would want to sleep here anyway. The Hoozu may or may not have been dangerous to humans, but either way sleeping in a room full of large carnivores would be unsettling.

She wanted a minute to talk to Shale and Fred about the next steps. She also didn’t want to stop here for too long. What if the Hoozu woke up? What if they smelled her and woke up? Hoozu breathed heavily while they slept, and their large nostrils were in an unusual place for quadrupedal mammals, halfway up the head almost between their eyes, rather than at the end of the snout.

Backing up into the turtle room didn’t seem like a better idea. But there weren’t even maintenance closets down here. All of the pipes and the wiring were exposed on the walls of the large, open rooms. Hera was used to being active and aggressive on missions, at least missions where all she had to deal with was humans or Gavidarians. But the Hoozu just made her wish there was somewhere to hide. Instead it seemed like she was doomed to be exposed, whatever she chose, just by the architecture of the place.

In that case, she might as well go forward. She moved as quickly as she could through the sleeping chamber while also remaining quiet. That wasn’t as hard as it could have been. The floors outside the alcoves were perfectly clean, and there was plenty of space. Whatever the Hoozu were, at least they weren’t slobs.

On the other side of the room there were three doorways, one very large one flanked by two smaller. Even the smaller ones were huge by human standards, but Hera hoped perhaps they were more likely to lead to somewhere she could stop and catch her breath out of the way of possible discovery. She took the one on the left.

Beyond the door, the corridor turned sharply left, was featureless for about thirty seconds’ walk, and then turned sharply right again. Hera was confused by the unused space until she took the second turn and realized that it was a noise baffle. Past that right turn it sounded like she was standing next to a major waterfall, loud enough that the Hoozu would want to keep the noise out of their sleeping quarters. But whatever she was hearing, all she could see was continuing, featureless white corridor walls. At least there were no Hoozu here, so she kept walking.

As she went, the sound got louder and louder, until she wished for her suit helmet, or at least earplugs. If Sage had lived in this part of the facility, they would have been deaf within weeks, if not days.

She had just wanted a safe place to talk to the team, but this wasn’t helping. Outside she couldn’t talk for fear of alerting the Hoozu. In here she couldn’t talk because no one would be able to hear her. At least she could message them, if she could make sure no Hoozu were sneaking up from behind. There was a room up ahead, and if it was empty she could find a corner to stand in. She could stand the noise for a few minutes while they figured out what to do.

While there was a room, it was one without any corners. Perhaps even calling it a room was inappropriate. It was either a circular room surrounding a sealed cylindrical core, or a hallway that circled around onto itself. Either way it was empty of Hoozu, and the central section was where the noise came from. Here there were control panels, access panels, and readouts, but she didn’t stop to try to make sense of them.

She put her back to the outer wall in a place where she could see the entrance she had come in by, and messaged Shale. “What is this place?”

“It’s the bottom of the water tube,” said Shale. “Be careful if you touch anything.”

She had seen the tube when they first arrived on the moon, but hadn’t expected to end up right next to it, at least not on this end. It was the main feature of Eddy, a reinforced pipe carrying water out of the subsurface ocean and into orbit for the faster-than-light ships. She’d been on that end a few times, but the few times she’d thought about this end, she’d pictured it farther away from where anyone lived. Even if the closest residents were Hoozu and not humans, it had to be dangerous, and it was certainly loud. Beyond that, the human operators of the treatment plant were only a short walk away.

Still, none of that really mattered right now. Surely no Hoozu would come to this loud room without good reason, so she probably had some time to ask the team how to face them. She could tune out the noise for a few minutes of message conversation.

“What do I do about the Hoozu?” she sent. “They scare me.” That was hard to admit, and apparently hard for Fred to believe, because he shot back an incredulous meme.

Shale was more sensitive. “You don’t scare easily,” said the AI. “What is it about them that bothers you?”

“They have huge heads,” said Hera, “and they’re full of sharp, pointy teeth.”

“Are you worried that they’re going to eat you?” said Shale.

“They ate this turtle,” said Hera. “I didn’t see it but I heard it, a snap and a splash and it was gone, shell and all. And I don’t even have a shell.”

“Are they fast?” said Fred.

“I haven’t seen one move, really,” said Hera. “They look ungainly on land. But so do alligators, and alligators are plenty fast.”

“If Sage was here,” said Shale, “if they lived here for years, then the Hoozu can’t be that dangerous.”

“Or maybe they were here for ten minutes and then got eaten by a Hoozu,” said Fred.

“Thanks,” said Hera. He sent a meme that was embarrassed and apologetic.

“One way or another,” said Shale, “we have to find out.”

“You want to trade places?” said Hera. “I bet Hoozu don’t look like your childhood playthings, only giant and full of teeth.”

“That’s probably what it is,” said Fred. “I’ve never seen you really scared of anything just because it’s big and mean. You weren’t scared of the space dragon.”

“Knowing that doesn’t really help when they make my legs shake,” said Hera.

“Just think of all the worst things that ever happened to a plushie,” said Fred. “Did you have a dog growing up? I had a dog.” And he sent an animated clip of a dog shaking its head and tearing a pink plushie to pieces.

“I’m not sure I want to think about a dog that big, either,” said Hera.

“Don’t think about the dog so much,” said Fred. “Just think about how sad it will be when one of the Hoozu is a bunch of pink fluff all over the room and its squeaker is sitting there in the open.”

Hera laughed at that. She wasn’t sure it was going to help, but at least it relieved the tension. “Do they have squeakers inside them?” she asked.

“I can’t tell from my files,” said Shale, which cracked both of the humans up. She could even hear Fred laughing over the sound of the rushing water.

“All right,” she said. “In the cause of science, I have to personally investigate. If I find Sage, that’s great, but my true mission here is now to find out if Hoozu have squeakers inside them.” Fred sent a meme that she interpreted as wishing good luck on the launch of an important mission. She braced herself and headed back out into the corridor she came from.

She was still nervous, but moving away from the noise helped, and so did continuing to think about squeakers. It was ludicrous, but it was also distracting, and her legs carried her back to the sleeping chamber just fine. Nothing much had changed there: still a few sleeping Hoozu, still none awake and alarmed. She found the courage to investigate the larger doorway out of the room.

The corridor behind the central door was short, broad, and didn’t curve at all. There were racks on the sides of it holding what looked like safety equipment if it were designed for Hoozu. There were even fire extinguishers built for large, clawed hands, though Hera couldn’t imagine when they might last have been charged. Not since the Gavidarians had been thrown out, at least, and probably not since the Gavidarians built the place. Although maybe the Hoozu were able to charge their own using chemicals extracted from the native water source.

Past the safety equipment racks a large circular room opened out, and in the middle of it was a pool of water. Hera didn’t get too close, both for fear that there might be Hoozu in it and because it was emanating extreme cold. This must be the access for the workers to get to the subsurface water reservoirs they were processing for use in the hyperdrives of interstellar commerce. She confirmed that impression by looking around the outside of the room, where tools for working underwater were hung along the walls, as well as big bags and barrels of chemical agents.

There weren’t enough of any of them, though. The tools might be explained by a lot of them being in use by the current shift. The ones remaining looked worn and in many cases barely functional. Rubber gaskets were wearing through, and pressure gauges on several different types of equipment were swinging wildly even though they were just being stored. But naturally the current workers would be using the most effective gear.

It didn’t seem like they could be using ninety percent of the chemical supplies, though, which is what seemed to be missing from the storage areas. There was space to stack a large quantity of bags, to store a large number of barrels, but the containers took up only a small fraction of the available space and looked pathetic. Hera wondered what the procedure for resupplying the Hoozu was, and if there were even any humans here who knew if there was a procedure at all. Had that been lost with the Gavidarians? Or was the facility administration just woefully behind?

Whichever it was, there definitely wasn’t any evidence of Sage to be found here. This space was both well-organized and threadbare, which made it very easy to search. Hera didn’t have to do much beyond a quick lap around the central pool to be sure that there wasn’t a human bishop anywhere in this room, or any evidence of one having been there. And surely there wasn’t any way they could have been inside the pool. Maybe it was comfortable for Hoozu, but Hera couldn’t imagine a human tolerating that water temperature for very long. She could barely handle standing next to it.

Even that cursory examination had kept her in the room too long to go undiscovered. Just as she was ready to leave a Hoozu burst out of the pool, followed by large splashes from two more. Hera leapt back in surprise, and to get away from the water, though she wasn’t quite successful at the latter. But it wasn’t an attack, just a very sudden exit from the underwater reaches of the facility. The Hoozu noticed her right away, and watched her, but they were more interested in removing their breathing apparatus and fetching large towels and drying themselves off. They were awkward handling the towels with their hands that were barely more useful than flippers, and with their mouths, but they managed to get dry well enough.

One of the Hoozu, noticing that they had gotten Hera a little bit wet with their splashes, brought her a towel held in its mouth. She only had to use a corner of it, but she was grateful for the opportunity to dry off, and even more grateful that the giant pink monsters seemed to be very far from hostile. When she was dry the Hoozu who had brought her the towel put its big head next to her, then turned it sideways so its chin was facing away, It sniffed her with those strange central nostrils, and must have found her acceptable. After it backed away the other two followed suit, apparently the Hoozu equivalent of a formal introduction.

They chuffed air at each other and moved their heads, arms, and shoulders in what was clearly body language, although being able to identify it as body language didn’t help Hera have any idea what it meant. She presumed they were discussing her, as definitely the oddest and most unexpected thing in the room to them, but she couldn’t puzzle out any meaning from it. She pinged Shale, but the AI was having as difficult a time as she was.

“The Gavidarians don’t know anything about Hoozu language,” they said. “They get their meaning across with whips and they don’t care about what gets said in return.”

Hera shelved the message and thought about how she could establish communication. If she couldn’t understand the Hoozu, maybe there was a way to get them to understand her. Not whips, though. The Hoozu might be frighteningly-shaped, but she was reminded that nothing was as frightening as a Gavidarian with no compassion for the species they were overseeing. Which was all Gavidarians, in her experience, at least if you didn’t count Shale.

Start with the easiest possibility. “I came here looking for another human who might have lived here with you,” she said, just in case maybe they understood human language. She didn’t have much hope of that, so she wasn’t especially disappointed when it attracted a little attention but achieved no communication.

One of the Hoozu came close again, and poked her with the side of its snout, making sure not to uncover its teeth or get them anywhere close to her. It then pointed toward the side of the room and lumbered over to one of the stacks of bagged chemicals. That at least was understandable, and when Hera followed it, she thought its body language looked pleased, even though she couldn’t say why. Maybe her subconscious was making progress that she couldn’t consciously identify. Or maybe she was inappropriately interpolating based on her cultural context. There wasn’t really any way to check which, so she just went with it.

The Hoozu made sure she examined the bags, then led her on to one of the tool racks, and some of the barrels. Each time it wanted her to look closely at them, to make sure she saw something about them. Unfortunately she couldn’t figure out what. But her expressions of confusion seemed as opaque to them as their own conversation was to her.

She kept sending to the team, but they didn’t have any more ideas than she did.

“At least they’re friendly,” said Jean.

“At least at the moment,” Hera sent back. “Do you think they’ll stay that way?”

“They never even thought about eating you when they came out of the pool,” said Fred. Which was the sort of thing he would notice. Hera had been too busy being scared and trying to get out of the way.

“I’m not sure we can trust that,” said Alistair, who had joined the channel.

“How’s it going up there?” said Hera.

“I told them I needed a bathroom break,” he said. “This is exhausting.”

“Talking about yourself is exhausting?” said Jean. “I’d think you would do less of it if that were true.”

“Thanks, Jean,” said Alistair. “I’m busting my butt to keep these people occupied and what do I get for it? Insults.”

“I don’t think anybody’s going to follow me down here,” said Hera. “You can make your excuses and get back to the ship if you want.”

“Thank Milo,” said Alistair fervently. “If I can figure out how to get them to let me go. Shale, can you fake an emergency or something?”

“Again?” said the AI. “I can’t do that every time you’re in an awkward spot.”

“I don’t see why not,” said Alistair. “But no, don’t worry, I can talk myself out of this. I’ll be back before too long.”

He dropped out of the channel, and Hera turned her full attention back to the Hoozu. They were conferring among themselves again, then one came and nudged her toward the sleeping chamber. There were a few things they wanted to show her in the hallway as well, though she wasn’t any closer to figuring out why.

Then they arrived back in the sleeping chamber and suddenly three Hoozu, who she’d gotten used to dealing with, were more than a dozen, and she was in danger of freaking out again. The Hoozu in the chamber were still asleep, but that didn’t seem to matter to Hera’s hindbrain. She took deep breaths and stood still, trying to calm herself.

The three Hoozu she had come in with didn’t seem to notice. Like in the other rooms in this section of the facility, there were supplies stacked against the edges of the room, between the sleeping alcoves. Either the designer of the Hoozu section had never heard of closets, or the Hoozu weren’t able to use them. She supposed doorknobs wouldn’t be the easiest thing with those hands.

The supplies were also like the rest of the facility in that there definitely weren’t enough of them. Hoozu domestic materials didn’t make immediate sense to Hera, though she supposed that if she had access to a Gavidarian museum they would be carefully labeled. Shale probably had that information, but it wasn’t very likely to be helpful. What was clear was that storage spaces originally intended to hold large amounts of the supplies were now almost empty. Her guide Hoozu directed her to several of them, but Hera still couldn’t make out what it wanted. She pinged Shale, but the AI said they couldn’t interpret anything from their encyclopedia of everyday items.

“And half of it is probably wrong anyway,” they said. “The Gavidarians are obsessive collectors but they’re not especially accurate. I’ve been cross-referencing the human data against what I got in Vexor Alexi and some of it’s quite funny.”

“No time for that now,” said Hera. “Save it for the next long space voyage.”

“If we ever figure out where to go next,” said Alistair, who had made it back to the ship.

At that point one of her guide Hoozu, gaining urgency in its desire to demonstrate whatever it was they were trying to tell her, knocked over one of the supply racks, which clattered to the floor. The largest sleeping Hoozu woke up suddenly, and its eyes happened to be focused right at Hera. It bellowed, loud enough to echo through the whole chamber, and the other sleepers began to awaken. And to notice her presence.

“Stay calm,” said Jean over the channel. “Stay calm. Stay calm.” The priest’s calming voice and steady cadence helped a little bit, but Hera was frozen in place. There wasn’t anywhere to go, and the Hoozu coming at her were fast, even just out of sleep. She tried to match her breathing to Jean’s continued mantra. In on “stay,” out after “calm,” don’t hyperventilate, they’re not going to eat you, you’re not a turtle no matter how much you want to pull your head and arms inside your shell right now. Against those jaws it wouldn’t help anyway.

One of her guide-Hoozu bellowed back, which must have been language, but it didn’t change the mass of Hoozu running at her. The largest one got there first, but its head didn’t come straight at Hera like she was expecting. Instead it stopped beside her just like the first one out of the pool had, though not as careful not to show its teeth. It did the same thing afterward as well, where it turned the top of its head sideways to smell her. Then it calmly got out of the way for its compatriots to take their turns.

By the time she had been sniffed all around, Hera had calmed down enough to think about how cute this whole thing probably was if you weren’t the person standing there terrified. Big pink furry animals with their heads cocked sideways to smell a human would probably be a hit with people who were sitting safely in their own homes. Fred was probably taking still photos to turn the whole thing into a meme.

If he was, at least he didn’t say anything about it. The channel was still just Jean repeating “stay calm” and Hera synchronizing her breathing to the beat. Eventually she got control over it again.

“I’m all right,” she said. “Thank you.”

“No problem,” said Jean. “Hopefully now they’ll all be as nice to you as the others.”

In fact most of them, after a group consultation with the three Hoozu who had originally discovered her, lay back down and attempted to go back to sleep. They weren’t fast sleepers, though, and most of them periodically opened an eye to look at her, or flared their nostrils to smell if she was still in the room. She wasn’t sure if that meant they saw her as a threat or not. A threat that her three guides had handled, perhaps.

She wasn’t sure if her guides finally realized how physically frightened she was, which would have been communication of a sort, or if they just didn’t want to fill up the smaller hallway with more than one of their huge bodies. But when they gave up on trying to get her to understand about the sleeping chamber, the first Hoozu she had encountered took her through the unexplored exit on the right side all by itself.

Like the other smaller hallway, this was a technical section. Unlike the other one it was a maze of cross-corridors, free-standing equipment, and small pipelines leading through the floor and the ceiling. Her Hoozu guide moved quickly through the maze, and Hera had a hard enough time following it to remember all the turns, let alone figure out what the equipment was for. She left tracking all of that to Shale.

“This is mineral extraction and purification,” said the AI. “Turning the Eddy water into ultrapure water for hyperdrives, and getting resources as a bonus.”

“Do the Hoozu operate and maintain the machinery?” asked Jean.

“Those controls weren’t designed for humans,” said Shale. “Or Gavidarians. The buttons are much too large, and the access panels have a lot of clearance space outside them, and no screws. They probably touch-open. I think everything here was built to be used by the Hoozu.”

“That’s a lot of technical work for a supposedly unintelligent species,” said Jean.

“Dogs can be trained to do a lot of work, too,” said Alistair. “Don’t jump to conclusions.”

“We’re not a first contact team,” said Fred. “We’re here to find Sage, remember? None of us is qualified to judge alien intelligence.”

“We might have to anyway,” said Jean.

“I don’t think Sage was ever here,” said Alistair. “Maybe not on Eddy at all.”

“Don’t jump to conclusions,” said Shale, mimicking Alistair’s cadence.

Hera didn’t have time to get in the middle of those two, not when she had to follow the Hoozu through the maze of equipment. Knowing all too well what their next few minutes were going to be like, she cut both of them out of her feed, sending Jean a private message to let them back in when they’d calmed down. At least the rest of the journey was mercifully silent, though Fred did send her a draft meme using one of the still photos from the sleeping chamber. Didn’t anyone on this team know how to concentrate on their work? Next time they found aliens with huge teeth she’d send Fred in to deal with them while she stayed on the ship and screwed around.

She was surprised when they reached the end of the technical maze and encountered a door, human-sized with a doorknob and everything. She’d lost track of her direction, but didn’t think it was likely this led back into the administrative part of the facility. And yet it clearly wasn’t there for the use of the Hoozu, who couldn’t fit inside even if they could manage the doorknob.

This time there wasn’t any trouble figuring out what it wanted her to do, at least. She opened the door into what seemed to have originally been a large utility closet of some sort. There was more equipment in here, but this had knobs and screws, small buttons and switches, things clearly designed to be used by smaller and more-flexible hands than the Hoozu possessed. It was a dead end, and Hera couldn’t imagine how a human was expected to walk all the way through the Hoozu habitat to do anything here. But she supposed a Gavidarian wouldn’t have that problem. Even those huge Hoozu teeth and powerful Hoozu jaws wouldn’t do much damage against a person made of solid rock.

It wasn’t a Gavidarian who had been living here, however. There were distinct signs that it had been modified for human habitation sometime in the past, and it still smelled a little like human, even though it was now empty. The inhabitant had taken most of their possessions with them, but there was some bedding, and a small table, and a jury-rigged hot pot that was just the right size for boiling a turtle. It looked like a lot of work had gone into making it, but Hera supposed there wasn’t much call for a turtle-cooker wherever Sage had gone next.

Because this could only have been Sage, and it was definitely not Sage at the present moment. The bishop looked to have been gone for months, at least, maybe since the end of the Occupation. If they had left here after the Gavidarians were gone it meant that, wherever they went next, it was a choice not to report back to the religious authorities, not a necessity.

Right in the center of the little table was a manuscript. It wasn’t as nicely constructed as the one from Ticonderoga, or nearly as large, but clearly Sage had left them a second hermitage text. Hera just hoped this one was more useful than the last had been.

She sat right there on the floor and started paging through it. Maybe taking it back to the ship would be better, but no Hoozu could get in here, and she could use a few minutes without them. It seemed unlikely at this point that they’d eaten Sage, unless somehow they’d let the bishop move out first. It also seemed unlikely that they were going to suddenly decide to eat Hera. But she needed a break anyway. And if Sage had spent a year down here, between Nike’s death and the end of the occupation, maybe they had learned how to communicate with the Hoozu. Maybe Hera could figure out what it was they wanted. After all, they’d given her the information she needed, even if they never understood that it was what she was looking for.

“That still looks very self-centered,” said Fred, who was reading over her shoulder. Alistair and Shale still hadn’t come back into the feed, though Jean was probably trying to calm them down now that Hera had found something significant.

“‘Coming here I’ve realized that all my years on Ticonderoga were wasted,'” Hera read out. “Well, they’re not wrong about that. ‘I know now that the true calling of my hermitage is not theology, but gaining a true understanding of these strange and noble creatures whose living space I have been forced to share.’ That could be useful.”

“In finding Sage, or in communicating with the Hoozu?” said Fred.

“Could be both,” said Hera. “Maybe the Hoozu know where they went.”

“Why would they?” said Fred. “Who leaves a forwarding address for animals who can’t send mail?”

“You’ve found everything you’re going to down there,” said Alistair, who was finally back in the feed. “Bring that back to the ship so we can analyze it.”

“I still need to find out what the Hoozu are trying to tell me,” said Hera.

“That’s not our mission,” said Alistair.

“He’s right,” said Shale. “Much as I hate to agree with him.”

“You can give me ten minutes,” said Hera. “Besides, I can rest here. The Hoozu can’t get to me. I’ll come back out when I can face them again. Until then I’m going to read this.”

“Skip to the end, at least,” said Fred. “Maybe Sage mentioned where they were going.”

Hera didn’t expect that in a hermitage manuscript, and she didn’t find it. She paged past several appendices before finding the last part of the narrative. The ending was interesting, though. “‘The Hoozu are beginning to run low on supplies,'” she read.

The Resistance has prevented Gavidarian attempts to bring in the materials they need to maintain their society. They’re beginning to get worried. There are rumors the Gavidarians are preparing to leave the Lexington system entirely, as amazing as that sounds. But if they go, there’s no telling who will supply the Hoozu.

The Hoozu have told me the most complete story I’ve been able to understand in all my time here. I’ve included as accurate a literal translation as I can in Appendix 4. But it was a story of past Hoozu colonies who had been transported to alien systems by the Gavidarians and then abandoned. They’re clearly convinced that they’re going to be left here, and I don’t know what the humans are likely to do about them.

If the Gavidarians really do leave, as hard as that is to believe in, I will have to do something about the supply situation. I don’t know what. The things I’ve learned about myself, in my meditations here and on Ticonderoga, make me reluctant to return to the ranks of the Church. It cannot be home for me anymore, even if a reconstituted power structure would be willing to have me.

But without the Church I have no power to assist the Hoozu, to find supplies for them and make sure they’re able to continue to survive here. It is a puzzle.

The manuscript ended at that point. If Sage had made a plan to help the Hoozu, the bishop hadn’t written it down. Or maybe Hera should stop thinking of Sage as “the bishop” at all. Perhaps there was something in the middle of the manuscript to indicate why Sage had rejected the idea of returning to their previous position in the Church, but there wasn’t time to look for it now. They could digitize the whole manuscript on the ship, and Shale could find anything significant faster than Hera could by simple reading.

Besides, whatever Sage had tried to do for the Hoozu supply situation, the former bishop clearly hadn’t succeeded. Hera hadn’t figured out what the Hoozu were trying to tell her because she thought it must be something she didn’t already know. But it was all about the poor state of maintenance of the facility, the lack of essential supplies for their habitat, and the wear and tear reducing the usefulness of their work gear.

Sage may not have been in a position to do anything about that, but Hera was. The facility administration would listen to her. Were begging to listen to her. At least, if Alistair hadn’t managed to screw that up by offending them all somehow. But even he would surely have mentioned if something like that had happened.

She tried to be reassuring to her Hoozu guide as they left the habitat, but she wasn’t sure how human body language would get through. Was putting a human hand on the top of that big head, next to those strange central nostrils, a gesture of reassurance to them as it would have been to her? It seemed like a natural thing to do now, and surely Sage would have done the same from time to time as they developed intimacy with the Hoozu. Hera’s heart rate still went up interacting with them, she still had to control her fearful impulses, and she couldn’t imagine what Sage must have gone through to suppress those urges and develop a communicative relationship with the Hoozu. That must have taken both skill and practice, another reason to hope they found the former bishop someday. Or perhaps the method would be somewhere inside the manuscript.

Her Hoozu guide left her at the end of the turtle chamber, another door that a Hoozu could neither open nor fit through. Were they trapped down here? They had access to the water, but a Hoozu wasn’t likely to do much better on the surface of Eddy than a human would. They had their own society, without interference, and they were obviously happy enough to keep running the water treatment equipment, or everything would have broken when the Gavidarian overseers left. But if they weren’t free to leave they were still slaves. It wasn’t only supplies they lacked, but freedom and self-determination. Hera couldn’t leave without doing something about that.

Alistair sure thought she could. And for once he had backup. Shale and Fred weren’t as abrasive about it as Alistair, maybe weren’t as convinced as Alistair, but they both wanted Hera to come right back to the ship, examine the manuscript, and take off on the trail of Sage if they could puzzle out where it led. They had no time for going back to the administration and arguing for resupplying the Hoozu.

Jean, usually the last to take a position on anything, wasn’t weighing in at all.

“We have to help these people,” said Hera as she was making her way through the empty parts of the human section.

“I still don’t think they’re people,” said Alistair.

“Because they don’t look like us? They have a language. They told Sage about their history.”

“I’m not convinced Sage was sane,” said Alistair.

“A few minutes ago you didn’t think they had been here at all,” said Hera.

“Well, I was wrong,” said Alistair. “The Hoozu clearly didn’t forge that manuscript.”

“If they had you’d have to admit they were people.”

“It’s possible they’re people,” said Fred, trying to create a break in the conflict. “We should send a message to Lexington. Get a xenoanthropologist out here. Someone who knows what they’re doing.”

“After we’ve digitized the manuscript,” said Shale. “We can send it along so they can start with everything Sage learned.”

“At least that’s not as much of a waste of time as what Hera wants to do,” said Alistair. “Come back to the ship and we’ll turn it over to the experts.”

“Who might take months or years getting here,” said Hera.

“Maybe there’s a xenoanthropologist already here,” said Fred.

“Doing what, growing zucchini?” said Hera. “Even if someone was hiding here, anybody with any expertise would have gone home after the end of the Occupation.”

“Except Sage, apparently,” said Jean.

“We don’t know where Sage went,” said Alistair. “That’s why we need to look at that manuscript now.”

“It can wait an hour,” said Hera.

“Can it?” said Alistair. “How do you know? Maybe being an hour late loses us the First Cup forever. And then what?”

“That doesn’t seem very likely,” said Fred.

“But we’re risking it for nothing,” said Alistair. “And an hour is going to turn into hours and then days and then weeks. I know you, Hera. You won’t stop until you think this pointless side quest is complete.”

“They need to be resupplied,” said Hera. “And soon.”

“We’ll tell the facility administrators,” said Alistair. “They don’t want the purification system to fail. They’ll fix it.”

“It’s not just about the purification system,” said Hera.

“So we’ll get an anthropologist in,” said Fred.

“Not good enough,” said Hera.

“Says who?” said Alistair.

“Says me,” said Hera. “And I’m the boss, remember? You agreed to that when you came back.”

“You’re wrong,” said Alistair.

“One of us is wrong,” said Hera. “And I’d rather be wrong and help out a bunch of semi-intelligent animals, if that’s really what they are, than be the one who’s wrong and leaves a community of intelligent people as slaves.”

“Especially when we’re responsible for the slaves,” said Jean.

“How could we be responsible for them?” said Alistair.

“Not us, personally, but us as representatives as Lexington,” said Jean. “If our government is holding slaves, if I even think our government might be holding slaves, I can’t ignore that. However important I think our mission is.”

“Of course you end up on her side,” said Alistair.

“Am I?” said Jean. “I’m not sure I am. I don’t enjoy this. I want to go looking for Sage. You’re right that she might get us stuck here working on this for a long time. But I took an oath to uphold the moral character of our culture, and I can’t just walk away without knowing if I’ve violated it. It would stick with me forever.”

“Until the xenoanthropologist got here,” said Fred.

“And then if they say we made the wrong choice? If we kept the Hoozu prisoners for months or years because it was more convenient for us that way? I’d be kicked out of the priesthood, and I’d deserve it. Maybe we find the First Cup in the meantime, but we’d be banned from ever pursuing the other Relics.”

“They won’t say we made the wrong choice,” said Alistair. “They’re not people.”

“I’m not as convinced of that as you are,” said Jean.

“It doesn’t really matter,” said Shale. “Hera’s right, she’s the boss. I agreed to that. Besides, I don’t know if you noticed, but she’s not talking to us anymore.”

Hera was pleased to hear Jean come into the argument, if not on her side, then at least on the side of pursuing the morally right path. But she wasn’t having this fight anymore, not with her own crew. She was the one in the facility, she was the one who could go to the administration, and however wrong Alistair thought she was, there wasn’t really anything he could do to stop her. He thought she was wasting time, and right now time was hers to waste.

The administrative staff had gone back to their jobs when Alistair finally gave up on telling them stories from the Resistance, but some of them noticed Hera coming back up from the depths of the facility. By the time she reached the head office she had a substantial following. Better to have an audience for this conversation, anyway. The more people heard her story, the easier the head administrator would be to convince.

And the people behind her were sympathetic to the Hoozu when she told her story, but somewhat surprisingly, so was the head administrator. Or at least he pretended to be. He wasn’t ready to concede that the Hoozu were people, but he was legitimately concerned about their supplies.

“The Gavidarians didn’t exactly leave us a manual for this place when they left,” he said. “We thought the Hoozu were self-sufficient. If they need something, we’ll provide it to them, if there’s some way to get us a list. There’s too much space traffic going through here to risk this place not running. And we want them to be as comfortable as possible.”

“I think there’s probably a list in this manuscript,” said Hera. “We need the original but we’ll send you any useful information when we digitize it. If not, you can send someone down there to figure out what’s missing. It’s all out in the open.”

“The Hoozu aren’t dangerous, then?” he said.

“They’re probably very dangerous,” said Hera. “They look very dangerous. But they’re smart, and they won’t hurt someone who’s not there to hurt them. Sage lived down there for a year and didn’t have any trouble.”

“The priest? I thought they died down there,” said one of the people behind Hera.

“No, they died after they left,” said another one.

Where were these people when she had first been asking? But if she’d heard them, and trusted them, she wouldn’t have the manuscript. She quizzed the staff while the head administrator turned back to his computer. Their stories never really lined up, but they all agreed that the priest who had been living with the Hoozu was dead. There was more myth to it than reality, but usually myth erred in the direction of dead people being still alive, not the other way around. If they all agreed Sage was dead, that seemed like a very plausible outcome. Which meant the manuscript might be all they had left to find their way to the First Cup.

When she was finished, the administrator was ready to talk to her again, though his demeanor had gotten less friendly. And her argument was about to get harder for him to accept.

“It’s not enough to resupply the Hoozu,” she said. “We’re keeping them slaves. And we can’t keep them slaves.”

“Mm-hm,” said the administrator.

“You’ll have to allow them to go free, and not just keep them working here,” she said.

“What does freedom for them look like?” said the administrator. “There’s not a lot of room on Eddy. This is a hostile planet and the only open water on it is the section they work in, that we keep liquid by the waste heat from returning ships. We can’t put amphibious creatures into human space quarters, even if the quarters weren’t much too small for them.”

“I’m not sure,” said Hera. “Maybe quarters will have to be built for them.”

“With what money?” said the administrator.

“With the money they’re being paid for their work, presumably,” said Hera. “With the back pay they’re owed since the Gavidarians left.”

“That’s not in my budget,” said the administrator. “Even if I wanted to do that, it’s impossible. I’ll send a message to my superiors on Lexington, but I don’t think they’re going to look too kindly on the suggestion.”

“I’ll send my own letter,” said Hera. “Maybe some pressure from the Church will help.”

“It might,” said the administrator. “But I’m not convinced it would from you.”

“What do you mean?”

“I just got a message from a ship coming here. They claim to have a representative from the Church. Which is just what you claimed to be. Are you really who you say you are?”

“I am,” said Hera. “And I think I need to get back to my ship to start digitizing this manuscript. I’ll send that message to your bosses.”

“No, I don’t think so,” said the administrator. “I think I’m going to keep you here until this other representative arrives and I can find out what’s going on.”

“You don’t think I could fight my way out past your staff?” said Hera.

“I’m sure you could,” he said. “But not if you wanted us to think you were legitimate. Not if you wanted anyone else to think you’re legitimate.”

He had a point.

“See, now you’re stuck there,” said Alistair. “For who knows how long.” She muted him. This was irritating enough without the I-told-you-sos. Besides, she needed to think about what a representative of the Church was doing there, and how she should respond to them. A priest might very well feel the same way Jean did about the Hoozu, and if not personally motivated to help them at least driven by the force of their vows. Then again there were factions in the church that might not feel the same way about that at all. Milo wouldn’t have liked it, at least not Hera’s perception of him, but as much as all the Church pledged themselves to Milo, they had very different opinions about what that meant. His teachings had been bent to slavery before, and worse.

Hera didn’t have to wait very long to find out what faction this priest represented. As soon as they showed up she knew, because it was a conservative priest she’d dealt with before: Kelly, who they’d thrown off their ship for stowing away on the way to Ticonderoga. Sent back to Lexington in an escape pod, which shouldn’t even have given them time to get here by now. What were they doing here? If they were still following Hera’s team, how did they know where to look? Not just what planet but what facility. But it was too amazing to be coincidence.

“How did they find us?” said Hera over her comm link.

“You filed a flight plan again,” said Fred.

“Of course I did, you can’t come to Eddy without a flight plan. There’s only one place to land. But Kelly should barely have made it back to Lexington by now. And how would they know to look in the water treatment plant?”

There was brief silence after that, then Fred said “Oh, come on, don’t start that again.”

“What happened?” said Hera.

“Alistair thinks Shale told Kelly where we are,” said Fred. “Can’t you hear Alistair?” Hera quickly unmuted him.

“It’s the only thing that makes sense,” said Alistair. “Somebody on this ship is leaking information. Would you rather I thought it was you?”

“I think we should hear what Kelly has to say,” said Hera. “Before we draw any conclusions.”